Format of data packets

This short article show what I have dissected from a winprinter or GDI printer to make it usable with ghostscript or other Linux tools. This kind of gadget is completely non standard as an excuse to make it cheaper, but also more convenient to its manufacturer and the commercial software monopolist, as they are very difficult to be interfaced. I plan to release also, in a later article, the techniques I have used to gain insights in its workings, if there are many interested people. Everything I have got my hands into are freely available in source code and with a handful of TTL integrated circuits and RT-Linux you can intercept everything going on at your parallel interface or printer port, even without a standard IEEE protocol. Another nice tool for exploring is Bochs, a Pentium emulator written by Kevin Lawton and sponsored by the Mandrakesoft, a Linux distributor. I will try to make all information contained here accurate and easy to follow, but I don't assume any responsability for the consequences or damages made for its use or misuse. In other words, no guarantees, please.

My winprinter is a Samsung ML-85G (G means GDI here), a Korean brand

better known for its video monitors, and is related as

paperweight

under the Printer-HOWTO entry. Otherwise, is a very beautiful piece of

hardware, reasonably fast (8 ppm) and silent as a laser printer allows, and

fully controllable by software (there isn't even a power switch!). Its only

drawback is being a GDI printer.

Well, things are going to change, at least

for this particular making of printer.

Wouldn't you like to explore yours too? Send an e-mail and let me discuss with you what you have. (Anyhow, I love to receive e-mails)

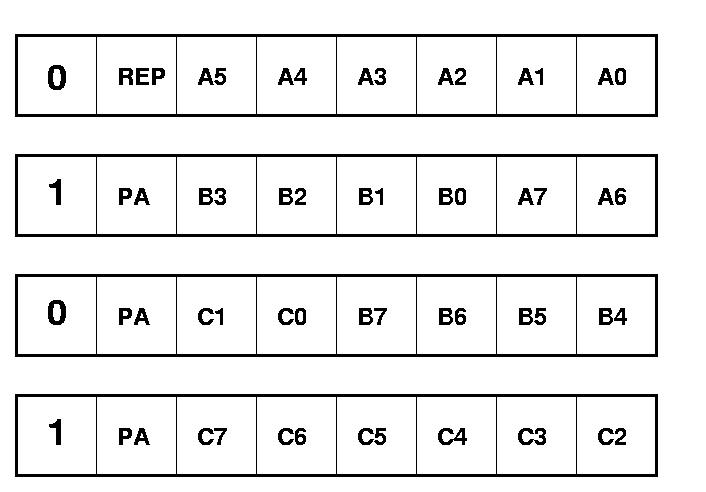

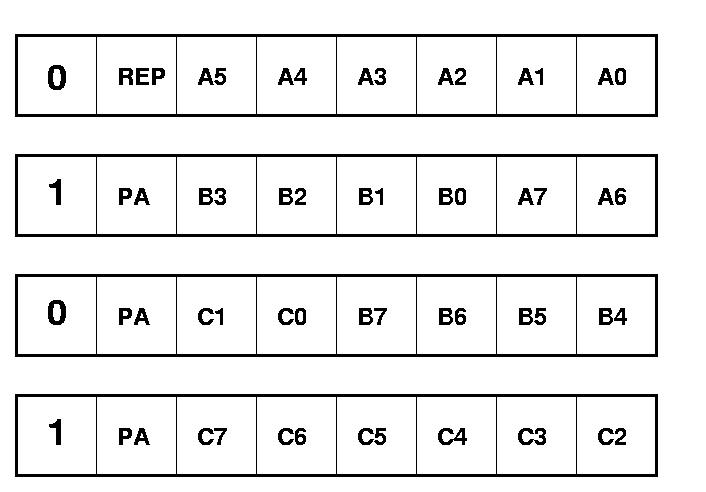

1. Each data chunk is composed of four bytes.

2. The first and third bytes have the MSB (most significant bit) zero, wheter the others have the same bit turned on.

3. Except for the first byte, all the others must have odd parity. The parity is the number of "ones" in the data it contains. To adjust the parity, the second MSB is used.

4. The first byte can be of two different kinds: (a) stream bits; or (2) RLE (run-length encoded) bits. This is selected by the second MSB bit of it. This is the only byte where bit-6 is not reserved for parity adjust.

Here is a sketch of the command word (4 bytes) for sending data to the

printer.

Format of data packets

|

Some examples may clarify better the compression algorithm.

Most pages are made of large white spaces with a few islands of painted

pixels. Those pages will be found with the packets (numbers given in hexadecimal

base) 7F-83-40-80. As you can see, the most significant

bits of the four bytes conform to the packet standard given above, and

REP=1 in the first byte (7F = 01111111b). So, we have a run-length-encoded

data, with the counter A = 11111111b+1,

or 256 (decimal). The data to be repeated is B = 00 and the byte to

be appended is C = 00 as well.

Then we will have this packet representing (256+1)*8 = 2056 pixels

of white space.

A more interesting example is given by 4D-B0-49-E0, representing a repeating pattern of 10011100b (where the 1 is a black pixel, and 0 is white) repeated fourteen times, followed by 10000000b (only the first pixel black).

In the next article, I will explain the other protocols for setting up the printer and checking its status. Of course, this other part will be needed for writing a driver for the domesticated monster. I would like to make known also that Samsung refused to give me technical information about the ML-85G. Maybe they even don't know how their printer work, or maybe they signed a contract with M$ for not releasing such information. Anyway, I don't require their information anymore.

Rildo Pragana <rildo@pragana.net>